"See what you started!"

In September 2024, Klassik Stiftung Weimar restituted a four-volume work to the granddaughter of Elsa von Klarwill, who had been persecuted by the Nazis. The case demonstrates how provenance research can open up a new chapter in a family’s history.

Provenance research consists primarily of a painstaking search for pieces to an incomplete puzzle. The first clue is usually a conspicuous entry in a collection register containing a wealth of information about a particular work. Such a find raises questions: Who did the object originally belong to and how did it enter the collection? Ninety percent of the time, researchers rely on the computer to search for objects and reconstruct the human fates behind them. To be sure, online information can help researchers determine instances of injustice, make decisions about restitution, and find heirs. But in many cases, such work can go far beyond the mere restitution of objects. It can set larger developments in motion and even help to forge new ties between people. The case of Elsa von Klarwill is one such example.

The case of Elsa von Klarwill

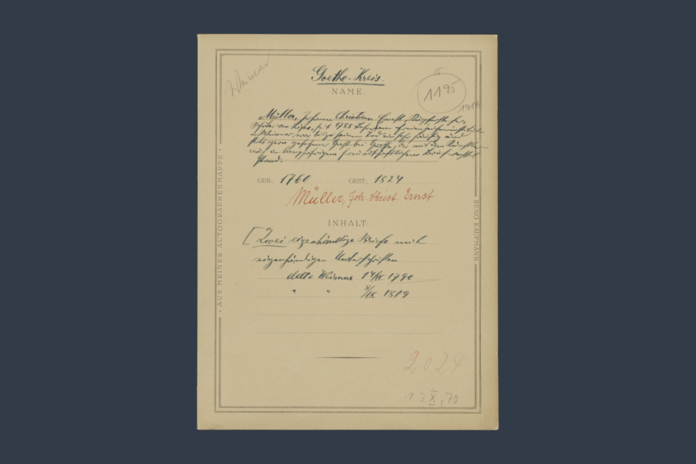

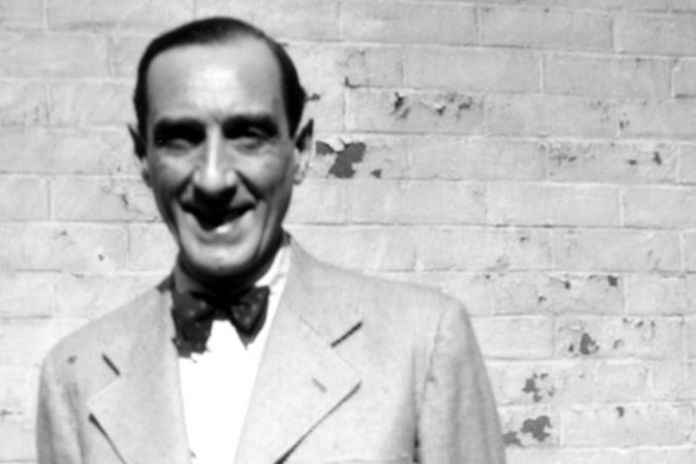

A systematical research within the holdings of Weimar’s Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek for cultural items confiscated by the Nazis uncovered a four-volume work acquired in September 1939 from the Königsberg antiquarian bookshop Gräfe und Unzer. The volumes, published in 1849–1950 by Alexandre Dumas, contain the memoirs of the French actor François-Joseph Talma. Thanks to a bookplate stamp in each volume, researchers discovered that the work previously belonged to the library of Viennese bibliophile Victor von Klarwill (1873–1933). The son of a Jewish writer and journalist ennobled in 1881, von Klarwill was a translator and publisher of French-language books who belonged to a circle of book collectors that would later become the Wiener Bibliophilen-Gesellschaft, the premiere society of book lovers in Austria. He was married to Elsa Elvira von Klarwill, née Egger (1877–1945), who was also Jewish. The couple had a son, Victor Isidor Ernst (1902–1984). When Victor senior died, in March 1933, Elsa von Klarwill became the sole heir.

After the annexation of Austria into the German Reich in March 1938, Elsa von Klarwill faced Nazi persecution. Among the repressive measures imposed on her was the requirement that she prepare a complete list of her assets. In the document that she submitted, dated 15 July 1938, she recorded “a private library (partly in French)” alongside household items and jewelry.

Her son, Victor, had left the country in mid-July 1938, emigrating first to Italy and shortly afterwards to Nairobi, Kenya. Elsa von Klarwill planned to follow him to Africa. In April 1939, she submitted an affidavit detailing her remaining assets.

The “Third Ordinance on the Basis of the Decree Regarding the Registration of Jewish Property,” issued on 21 February 1939, required Elsa von Klarwill to sell her jewelry and other precious metals. A document dated 14 April 1939 from the Public Purchasing Office of the Dorotheum auction house in Vienna lists the items that Elsa was forced to sell. The Viennese authorities noted Elsa’s departure on 31 October 1939. She travelled directly to her son in Kenya and settled there.

It is no longer possible to reconstruct when and how the four volumes formerly owned by Elsa von Klarwill entered the antiquarian book trade. The headquarters of the Königsberg bookshop from which the Thuringian State Library acquired the volumes in 1939 was destroyed during Allied air raids on the city in August 1944. Furthermore, no evidence exists indicating that Elsa von Klarwill sold any of the books from her husband’s private library before 1938. In view of the close chronology of events – Elsa submitted her affidavit of assets in July 1938, the Thuringian State Library issued a receipt for the four volumes in September 1939, and Elsa emigrated in October 1939 – the Klassik Stiftung Weimar decided to treat the books as looted items and return them to the heirs of Elsa von Klarwill. In this, the Klassik Stiftung Weimar followed the Washington Principles of 1998, which state that “every effort should be made” to identify the heirs of pre-war owners and achieve just and fair solutions.

The search for heirs

The search for heirs often marks the next – and in many cases more challenging – stage of provenance research. Family networks are complex, and after many decades descendants can often be scattered around the world. Fortunately, in the case of the von Klarwill family, researchers quickly found a heir. The search was aided by genealogical databases and the information recorded in family trees. After emigrating from Vienna, Elsa von Klarwill lived with her son Victor and his wife in Nairobi. Elsa von Klarwill died on 8 April 1945, the same day that her granddaughter Victoria Elsa was born. After the Second World War, the family operated a lodge at the foot of Mount Kenya and organized safaris for tourists, but had to leave the country in the 1950s when an anti-colonial rebellion broke out against the British authorities. The family first moved to South Africa and a little later to England. When Victor died there in 1985, Victoria Elsa became his sole heir. She moved to Canada at the end of the 1960s, as England seemed too small and cramped after her early childhood in Africa. Today she lives with her family near Vancouver.

More than one case of restitution

Researchers in Weimar made contact with the family, and soon an intense and friendly correspondence began. The family provided more information about the persecution of their forebears. Spurred by the research carried out by Klassik Stiftung Weimar, the family experienced what they called a ‘chain reaction’ as they began their own research into the fate of the book collection. Inquiries at other institutions bore fruit: the family found one volume in the library holdings of the Freie Universität Berlin, which was restituted to them in September 2024. They found another at the Vienna City Library (formerly known as the Vienna City and State Library).

“See what you started!”

In September 2024, Elsa von Klarwill's granddaughter, now 79 years old, travelled to Weimar with her two daughters. The family decided that the four volumes should remain in the Duchess Anna Amalia Library and accepted the purchase price offered by Klassik Stiftung Weimar. During their visit to Weimar, the family said that the work of Klassik Stiftung Weimar had inspired them. Two of Elsa von Klarwill's descendants now intend to research the fate of their family and its property during the Nazi era and to publish their findings.

In the case of Elsa von Klarwill, provenance research at the Klassik Stiftung Weimar led to more than a mererestitution of looted volumes to their rightful owners. It encouraged the family to dive deeper into its past and in the process strengthen ties among its members, especially those still living in Austria. As Elsa von Klarwill's granddaughter wrote on 3 September 2024, shortly before her visit to Weimar: ‘We will have many stories to tell you of the ball that your research has started to roll! ...See what you started!’

Write new comment