The Case of Beno Kaufmann

Klassik Stiftung Weimar has restituted 39 letters, a handwritten poem, and a manuscript folder to the heirs of Beno Kaufmann, a Dresden art collector who was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. The case represents the largest collection of Nazi-looted cultural assets to be discovered in the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv to date.

In February 1942, the Berlin art and manuscript dealer Karl Ernst Henrici (1879–1944) sent a bundle of historical letters to the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv. The letters came “from a very large collection” that Henrici had recently acquired; the authors and recipients were “all in some way connected to the period of Weimar Classicism.” In later correspondence, Henrici did in fact mention a “large Kaufmann collection,” but these objects were not attributed to Kaufmann. The Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv ultimately purchased the collection, which consisted of 21 letters and a handwritten poem. As part of this purchase, a list of the acquired items was created, with details regarding each object.

The Thuringian State Library in Weimar also made a purchase from Henrici, buying 27 letters in February 1942. The record of acquisitions maintained by the library describes the letters only briefly: “Letters to the librarian Kräuter, from Stickel and others.” The addressee in this case was the Weimar librarian Friedrich Theodor David Kräuter (1790–1856), who also worked as Goethe’s secretary. One of the senders was Johann Gustav Stickel (1805–1896), a professor at the University of Jena and the director of the university’s Grand Ducal Oriental Coin Cabinet. No further details about these letters could be found in the surviving correspondence between Henrici and the Thuringian State Library.

As these items of unclear origin were purchased during the Nazi era, they were flagged for greater scrutiny by provenance researchers at Klassik Stiftung Weimar. A core responsibility of the foundation’s provenance researchers is to review the items held in Weimar’s archives and museums for possible misappropriation, particularly with a view to acts of confiscation by the Nazis.

From among the 49 handwritten documents flagged by the researchers, only 40 letters and the poem could be clearly identified, due to the imprecise descriptions contained in the official inventory documents and purchase records. Thirty-nine of these letters and the poem were identified in the holdings of the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv to which a large part of the State Library’s manuscript collection was transferred in 1969. The researchers also identified an additional letter from the Kaufmann collection, which had been transferred to the Weimar State Archive in 1984.

Provenance researchers carefully examined the letters held by the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv. One important step was to search for any clues or indications of previous owners. However, in contrast to paintings, prints, or books, handwritten documents such as letters rarely feature ownership stamps, labels, or notes, as manuscript collectors are loath to spoil the original state of a document. Instead, collectors typically place manuscript collections in folders or envelopes and record their notes regarding the contents on the outside cover.

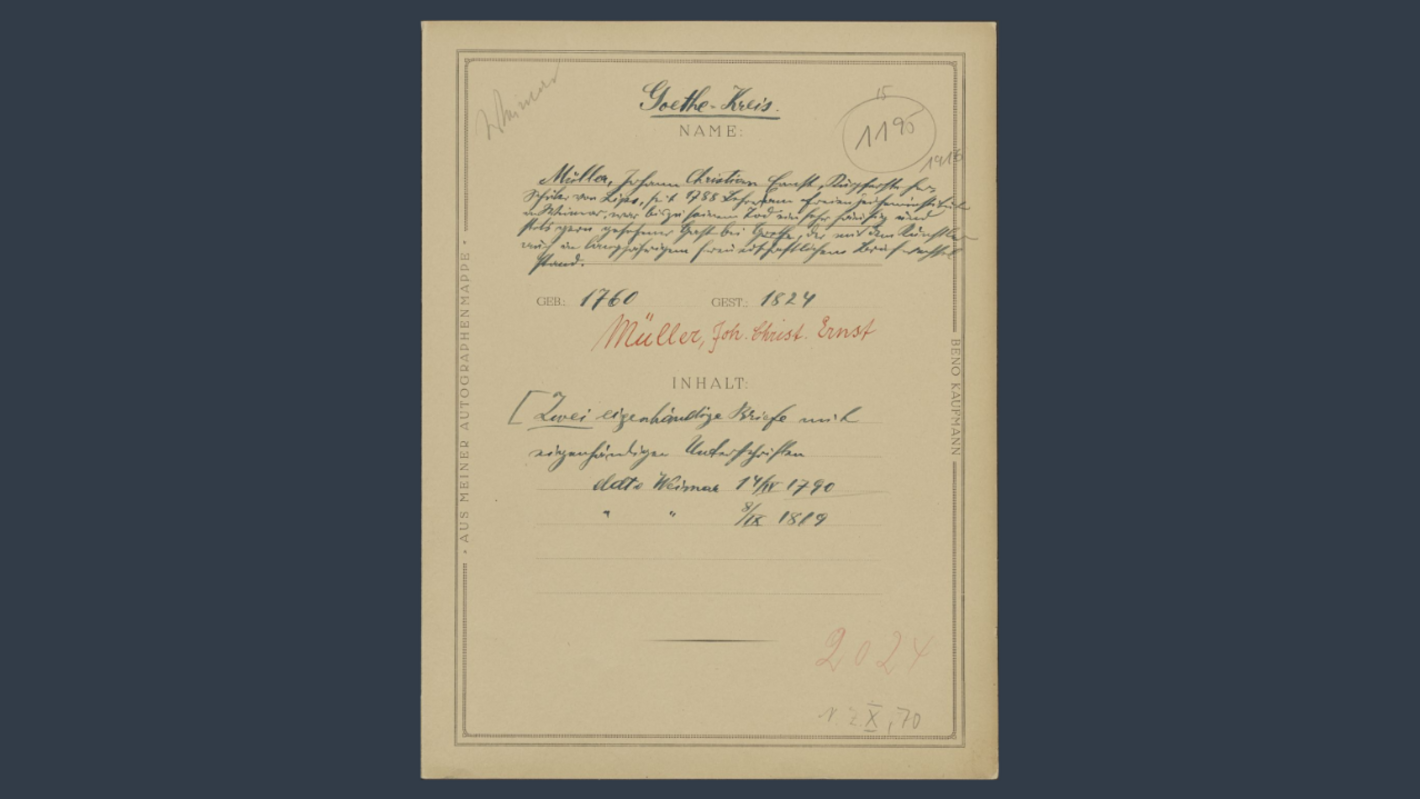

Researchers at Klassik Stiftung Weimar discovered that the letters acquired by Henrici in 1942 were originally placed in cardboard folders. These folders were adorned with a custom border that included the words “From My Manuscript Portfolio” printed vertically on the left edge and “Beno Kaufmann” on the right edge. They also featured the handwritten note “Goethe-Kreis” to indicate proximity to Goethe. Information regarding the authors, recipients, and contents of the letters were noted beneath. Sometimes the folders also featured information about when and from whom the manuscripts were acquired. Unfortunately, these folders were separated from the objects during conservation measures at the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv. In some cases, copies of the folders were made; in others, information about the folder was recorded in the archive’s inventory. Only one of the original folders has survived.

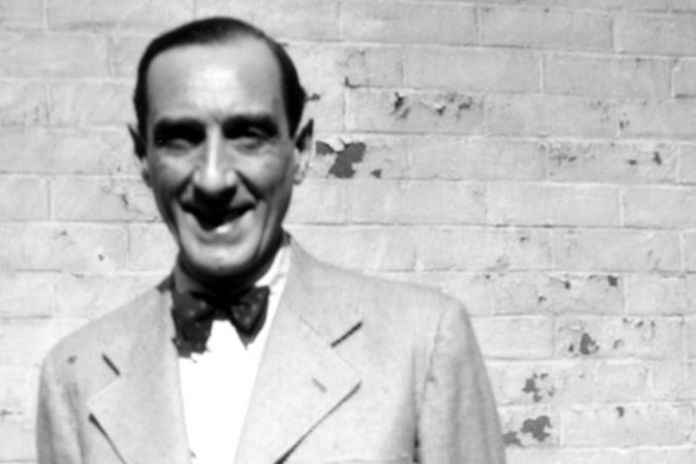

But who was Beno Kaufmann? What do we know about his life?

Beno Kaufmann’s manuscript collection focused on the period of Weimar Classicism. The dates on the folders show that he was still active as a collector at the beginning of the 1930s. In the effort to bring additional clues to light, researchers investigated the art world during this period, with a particular focus on Kaufmann’s area of interest.

A persecuted collector

In 1932 major celebrations took place commemorating the 100th anniversary of Goethe’s death. Alongside cultural festivals, theater performances, radio broadcasts, and readings were numerous exhibitions. In Dresden, the Sächsischer Kunstverein (Saxony Association of the Art) organized an extensive exhibition. The provenance researchers uncovered a decisive clue in the historical exhibition catalog: among the meticulous lists recording the many loaned objects and their owners was mention of a “Director Beno Kaufmann” from Dresden.

The provenance researchers confirmed that Beno Kaufmann was a victim of Nazi persecution by studying address books from 1920s and 30s Dresden as well as various records of Jewish victims of the Nazi regime. Inquiries placed with provenance researchers in Dresden resulted in a cordial exchange that brought additional details to light concerning Kaufmann’s fate.

Beno Berl Kaufmann was born on 10 March 1862 in Krakow, Austria (now part of Poland). At the beginning of the 20th century he lived in Berlin and worked as a newspaper editor. In 1903, he married Anna Scharl, an Austrian native. The couple then moved to Dresden around 1923. Beno Kaufmann is listed in a local address book as having the occupational title of “factory director,” but the company in question could not be identified. Anna Kaufmann died at the end of the 1930s. The exact date of her death could not be determined. On 19 June 1942, at the age of 80, Beno Kaufmann was forcibly transferred to the sanatorium Israelitische Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Bendorf-Sayn near Koblenz with a diagnosis of “senile dementia.” One month later, on 27 July 1942, he was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. He subsequently died on 12 August 1942. The exact circumstances of his death are not known.

The exhibition catalog from 1932 shows that Beno Kaufmann not only collected letters, but also owned rare books and prints. Archival documents in Koblenz dating from 1943 and concerning the planned Führermuseum in Linz mention coins confiscated from Jews that were to be transferred to the new museum. These documents refer to the “Collection of Benno [sic] Berl Israel Kaufmann in Bendorf/Sayn (formerly Dresden),” which had been confiscated by the financial authorities in Dresden. Due to war-related losses, many of the case files created by the financial authorities regarding the confiscation and sale of Jewish assets are missing from archival records. However, the evidence found in the Koblenz archives about Beno Kaufmann’s coin collection indicates that his other collections were also confiscated by the Nazis. The Kaufmann manuscripts acquired from Karl Ernst Henrici in 1942 were thus deemed to be Nazi-confiscated assets. In line with the Washington Principles of 1998, such assets are to be restituted to their rightful heirs.

The search for heirs and successful restitution

Beno Kaufmann had no children, but he did have five siblings, four nieces, and three nephews. Many of his family members were murdered in the Holocaust, though some managed to escape Germany. After a prolonged investigation, researchers identified two grandchildren who had descended from one of Beno Kaufmann’s brothers. Both resided in the US. Sometime later, a great-grandson of another brother was identified, who also resided in the US. The Holocaust Claims Processing Office, a New York state agency, helped to establish contact to these individuals. Up to this point in time, the descendants were unaware of each other and also knew very little about their family history. Like so many Holocaust survivors, their parents and grandparents had not found the strength to talk about the trauma of the war years. Learning about this history was an emotionally moving experience for Kaufmann’s relatives and their families. In the process, they got to know one another and discussed the future of the restituted manuscripts in Weimar.

Provenance researchers from both Weimar and Dresden were involved in the case. Information shared with institutions in Frankfurt/Main and other institutions in Weimar led to the discovery of additional objects from Kaufmann’s manuscript collection. Klassik Stiftung Weimar spearheaded the restitution process and the search for heirs. Three additional institutes participated: the Dresden State and University Library, the Freie Deutsche Hochstift in Frankfurt/Main, and the Thuringian State Archives. In total, 66 objects were returned to their rightful heirs. The letter transferred to the Weimar State Archive in 1984 was given to the heirs at their request, along with the last remaining original folder featuring Beno Kaufmann’s handwritten notes. The remaining manuscripts were purchased by the other participating institutes, and are now legally part of their collections. Thanks in part to the spirit of cooperation shown by the involved parties, the outcome of the restitution process proved satisfying for everyone. A brass commemorative cobblestone known as a Stolperstein will be installed in Dresden to honor the memory of Beno Kaufmann.

Write new comment